The Anglo Zulu War of 1879 was a short but remarkable war, which saw the greatest single loss suffered by a modern army against a native army. Most people are aware of the film ‘Zulu’, starring Stanley Baker and Michael Caine, which portrayed the epic stand of 140 men of the 24th Regiment of Foot, who defended the mission station at Rorke’s Drift against repeated attacks by a force of over 3,000 Zulus for over twelve hours, however, events leading up to this gallant stand are somewhat less well publicised.

South Africa was being settled by white Europeans, mainly Dutch and British colonists, but was still dominated by native tribes, such as the Zulus, who were ruled over by King Cetshwayo. During 1874 Sir Henry Bartle Frere was sent to South Africa in the post of High Commissioner, to oversee the integration of these factions, and create a federation under the control of the British Empire. The main obstacle was the presence of the independent states of the South African Republic and the Kingdom of Zululand, and the Zulu army of 40,000 warriors. On 11 December 1878, Frere, without authorisation, issued an ultimatum to Cetshwayo, containing thirteen separate demands including the disbandment of the Zulu army, which the Zulu King did not comply with.

As a result of this non-compliance, Frere ordered Lord Chelmsford, the commander of the British troops in South Africa, to invade Zululand, and on 11 January 1879 a 5,000 strong British force crossed the Orange River and entered Zululand at Rorke’s Drift. Chelmsford had no respect for the Zulu army, and was sure that his troops were vastly superior in terms of arms, which they were, and training. This confidence was strongly felt within all of the troops, and proved to be a terrible misjudgement on the fighting qualities of the Zulu army.

By 20 January the column had only advanced eleven miles, and had set up camp on slopes of a hill called Isandlwana. Early in the morning of 22 Janary 1879, Chelmsford set off with the bulk of his force to pursue the Zulu army, which he believed was gathering to the south-east. Full of confidence, he failed to ensure adequate reconnaissance of positions to the north-east of Isandlwana, where an army of 20,000 Zulu warriors were waiting.

At around 08.00 mounted troops spotted the advancing Zulus, and reported their movement to Chelmsford, but he arrogantly failed to spot the danger in their movements, and carried on with his move, leaving around 1,300 men, mainly of the 24th Regiment of Foot (later the South Wales Borderers), plus about 450 other men, to guard the camp at Isandlwana.

At 11.00 the main Zulu impi was again spotted by mounted troops, and realising that their advance had been spotted, the Zulus began their attack, using their traditional tactic of encirclement known as the ‘horns of the buffalo’, and a desperate defensive action began.

While his garrison was desperately fighting against overwhelming odds, Chelmsford again threw away a chance to save his men, assuming that his messages had been a false alarm. After four hours of terrible fighting, the Zulus had captured the camp. The Isandlwana battlefield was strewn with the bodies of 1,350 British soldiers and native levies. The 1/24 Regiment of Foot had been wiped out, save for a small number who were at Rorke’s Drift.

It was an embarrassment and a tragedy rolled into one. The greatest loss suffered by a modern army against a native foe.

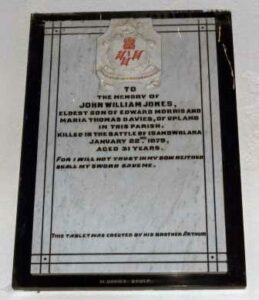

One of the men killed at Isandlwana was from the small village of Llandefeilog, in Carmarthenshire. John William Jones Davies was born in Upland, Llandefeilog 1849, the son of the wealthy landowner Edward Morris Davies and Maria Thomas Davies (née Jones). (He is possibly the man who served with the 2nd Battalion, 24th Foot as a Private, with the army number 743.) John was thirty one years old when he was killed at Isandlwana on 22 January 1879 and is among the casualties buried in scattered mass graves on the battlefield. There is a memorial in his memory within St. Maelog’s Church at Llandefeilog. (Photograph courtesy of Paul Bradly).

Later during the day, a breakaway force of 3,000 Zulus attacked the mission station at Rorke’s Drift, which was being lightly held by 140 men of B Company of the 24th Foot. Survivors from the Isandlwana debacle had reached Rorke’s Drift earlier in the afternoon, to warn the garrison of the impending attack, giving the garrison commander, Lieutenant John Chard, of the Royal Engineers, time to prepare his defences.

At around 16.20 the Zulu attack began, and piecemeal attacks continued throughout the night. The details of the brave defence are well portrayed in the film ‘Zulu’, which is quite historically accurate for a war movie, give or take some major alterations of facts!

As dawn broke, the garrison was pleased to see that the Zulus seemed to have withdrawn, and all that could be seen was the battlefield, strewn with Zulu dead. An Impi of Zulus appeared on the horizon, spreading despair throughout the garrison survivors, but they withdrew, much to the relief of the men, and hours later, Chelmsford’s relief column reached Rorke’s Drift.

Casualties among the defenders had been remarkably light. The 1st/24th Foot suffered four men killed or mortally wounded, and two more wounded. The 2nd/24th Foot suffered nine killed or mortally wounded, and a further nine wounded, while three other men of the Natal Native Contingent, Commissariat and Transport Department and the Natal Mounted Police were killed.

The bodies of 351 Zulus bodies were counted on the battlefield, but there are rumours of a further 500 wounded and captured Zulus being massacred by the incensed British.

Partly in an attempt to counter public dismay at the losses at Isandlwana, the importance of the defence of Rorke’s Drift was exaggerated, and eleven Victoria Crosses and four Distinguished Conduct Medals were awarded to the heroic defenders of Rorke’s Drift.

Awarded the Victoria Cross:

Lieutenant John Rouse Merriott Chard. 5th Field Company, Royal Engineers

Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead. B Company, 2nd/24th Foot

Corporal William Wilson Allen. B Company, 2nd/24th Foot

Private Frederick Hitch. B Company, 2nd/24th Foot

Private Alfred Henry Hook. B Company, 2nd/24th Foot

Private Robert Jones. B Company, 2nd/24th Foot

Private William Jones. B Company, 2nd/24th Foot

Private John Williams. B Company, 2nd/24th Foot

Surgeon James Henry Reynolds. Army Medical Department

Acting Assistant Commissary James Langley Dalton. Commissariat and Transport Department

Corporal Christian Ferdinand Schiess. 2nd/3rd Natal Native Contingent

Awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal:

Gunner John Cantwell. N Battalion, 5th Brigade, Royal Horse Artillery

Private John William Roy. 1st/24th Foot

Colour Sergeant Frank Edward Bourne. B Company, 2nd/24th Foot

Second Corporal Francis Attwood. Army Service Corps

The one known West Walian to have served at Rorke’s Drift, and have been lucky enough to survive, was Private Thomas Collins, from the small village of Camrose, near Haverfordwest. Little is known of the life of this man, but his home village proudly displays two bronze plaques, which commemorates this brave man, who is buried in an unmarked grave at an old Asylum in Newport, Gwent.

The Hon Ronald George Elidor Campbell, Captain, Coldstream Guards. Ronald was born at Stackpole Elidor on 30 December 1848, the second son of the Earl of Cawdor, John Frederick Vaughan Campbell, and of his wife, Sarah Mary Compton-Cavendish. He was educated at Eton and joined the army in 1867 as an ensign in the Coldstream Guards. In 1871 he became lieutenant and captain and was appointed adjutant in the same year. He embarked for South Africa in November 1878, and was appointed staff officer to Colonel Evelyn Wood, whose column was forming on the Transvaal frontier, in readiness for the invasion of Zululand. The column crossed the Blood River on 6 January 1879, and took part in various operations against the Zulus. On 28 March 1879 the British attacked a large Zulu force on Hlobane Mountain in order to create a diversion from their main assault on Isandlwana. Robert was riding with a party of officers who advanced towards the summit, but came under fire from the Zulus who had been armed with rifles captured during the Isandlwana massacre. One of the men with Robert, Llewellyn Lloyd, fell from his horse mortally wounded, so Robert dismounted and attempted to pull him to safety. He then led several men in a charge on a cave but was shot dead. Both Robert and Lloyd were buried on the Hlobane Battlefield, where their graves still lie today. Sir Evelyn Wood later stated that if Robert had survived, he would have recommended him for the Victoria Cross. Sadly the award was not posthumously awarded at that time. Thirty-seven years later his son, Major John Vaughan Campbell, won the Victoria Cross, during the Battle of the Somme. Robert is commemorated on a fine marble memorial inside the family church at Stackpole Elidor.

Charles Evelyn Mason, Lieutenant, 3rd Regiment. Charles was born in Laugharne in 1855, the son of George William Mason and Marianne Atherton Mason (nee Mitford). The family lived in Laugharne for over ten years before moving to Morton Hall, near Retford, Nottinghamshire. His mother was the daughter of the retired Captain Joseph George Mitford, late of the Indian Army and the East India Company, who had retired to Laugharne in the 1840’s and bought The Parsonage, near the Church. She had married his father at Laugharne in 1844. Charles was educated in England before gaining a commission as a Sub Lieutenant on 21 September 1874 and joined the 3rd Regiment of Foot (East Kent Regiment, The Buffs). He embarked with the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Regiment for service in South Africa. Following the defeat at Isandlwana Lord Chelmsford reinforced his army and led a further expedition across the Tugela River in March 1879 to relieve besieged troops in Eshowe. Charles was most probably with his battalion during this relief expedition which resulted in the defeat of a large Zulu impi on 2 April 1879. He survived the battle, but died at the Base Hospital at Herwen on 7 April 1879, aged 24. Charles was buried in Stanger Cemetery, KwaZulu Natal, near a town which is now called KwaDukuza. He is commemorated on a war memorial inside Canterbury Cathedral, alongside the other Zulu War casualties of his regiment. A brother, Arthur James Mason, was Canon of Canterbury Cathedral for many years.

The war continued briefly, but the most amazing aspect was that Queen Victoria backed Lord Chelmsford, who attempted to push the blame onto Colonel Durnford, who had been killed at Isandlwana, and also began to claim that a shortage of ammunition had led to the massacre. The clamour for Chelmsford to be recalled to England got so great that the Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, was forced to act against Victoria’s wishes, and threatened to replace Chelmsford with Wolseley.

However, the British captured King Cetshwayo in August 1879, and the war was brought to an end. While the British had lost face, Cetshwayo was exiled, and Zululand was broken up. The campaign to confederate South Africa had to wait for over twenty years, until the Second Boer War.

Disraeli lost the 1880 election and died the following year, while Lord Chelmsford was showered with honours by Queen Victoria and feted as a hero. The real heroes, the dead of Isandlwana and the defenders of Rorke’s Drift, sadly faded into anonymity.